![]()

In the folklore of various cultures and ancient civilizations, rabbits have long represented a kind of Trickster figure. In Chinese, Japanese, and Korean mythology, rabbits live on the moon. The Aztecs worshipped a group of deities known as the Centzon Tōtōchtin, a group of 400 hard-partying rabbits who were the gods of drunkenness. And in a slightly more recent mythos, bunnies were the bête noir of a certain thousand-year-old former vengeance demon.

As we head into the Easter weekend, I’d like to take a minute to revisit this venerable list—slightly updated for 2023, the Year of the Rabbit!—paying tribute to some of the more memorable bunnies and assorted rabbit-like creatures who have hopped, time-traveled, and occasionally slaughtered their way through science fiction and fantasy, beginning (in no particular order), with everybody’s favorite hard-drinking, invisible lagomorph….

Harvey

Based on a Pulitzer Prize-winning stage play, Harvey embodies everything strange and brilliant and wonderful about classic Hollywood. Jimmy Stewart stars as good-natured kook Elwood P. Dowd, who spends his days at his favorite bar in the company of his best friend, Harvey, an invisible, six foot, three-and-one-half-inch tall talking rabbit. Technically speaking, Harvey is a pooka (or púca), “a benign but mischievous creature” from Celtic mythology with a pronounced fondness for social misfits—but since he takes the form of a giant rabbit, he totally makes the list. Driven by Stewart’s delightful and deeply touching performance, Harvey is a lighthearted comedy with unexpected depths, an inspiring piece of fantasy that celebrates the triumph of a kind-hearted nonconformist over worldly cynicism and the pressures of respectability.

Bunnicula

![]()

In 1979’s Bunnicula: A Rabbit-Tale of Mystery, the Monroe family find a baby rabbit one dark and stormy night during a screening of Dracula, but the family’s other pets are suspicious of the furry foundling, with its strange markings and fang-like teeth. When vegetables start turning up mysteriously drained of their juice, the family cat springs into action with the zeal of a fanatical, feline Van Helsing. Chronicling the adventures of the Monroes through the eyes of Harold, the family dog, the Bunnicula series spun off into seven books, ending in 2006 with Bunnicula Meets Edgar Allan Crow (although my favorite title in the series has always been The Celery Stalks at Midnight). There’s even a cartoon series based on the books, which ran for three seasons between 2016 and 2018.

Frank (Donnie Darko)

Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko quickly gained a huge cult following after it was released in 2001 (and since then seems to have generated a certain amount of backlash), but whether you love it or think it’s completely overrated, I think we can all agree that Frank is probably the creepiest rabbit-type-thing on this list, appearing to the title character in a series of visions like in the form of some kind of menacing demon-alien terror bunny. According to many readings of the film, creepy rabbit Frank is actually the dead, time-travelling version of his sister’s boyfriend, Frank, who is manipulating Donnie into saving the universe. Okay, it’s complicated—if you want a rundown of the film’s timeline, go here—but all you really need to know is that if Frank shows up on your doorstep with a basket of Peeps and jellybeans, you should probably run for the hills and don’t look back. (The movie also gets a bonus point for employing Echo & the Bunnymen so effectively in its opening scene…)

Hazel, Fiver, et al. (Watership Down)

Richard Adams’ brilliant heroic fantasy features a group of anthropomorphic rabbits complete with their own folklore, mythology, language, and poetry. Jo Walton has discussed the book at length, although I was initially introduced to Fiver, Hazel, and company through the animated film version; as a seven-year-old, I found it equal parts disturbing and fascinating (and I’m apparently not the only one—in writing this post I ran across a Facebook group called “Watership Down (the film) traumatized me as a kid!”). Maybe it’s not surprising, then, that both the book and its film adaptation are discussed in Donnie Darko…

The Killer Rabbit of Caerbannog (Monty Python and the Holy Grail)

The Killer Rabbit of Caerbannog probably needs no introduction—in the immortal words of Tim the Enchanter, it’s the most foul, cruel, and bad-tempered rodent you ever set eyes on. Apparently inspired by a medieval carving on the façade of France’s Amiens Cathedral (in which the vice of cowardice is represented by a knight fleeing from a rabbit), this scene is now a permanent contender for the title of greatest two minutes in bunny-related movie comedy history…

Roger Rabbit

Gary K. Wolf’s original novel, Who Censored Roger Rabbit? is significantly different from the blockbuster Disney hit it was eventually turned into. For example, the novel was set in the present day (and not the 1940s), the cartoon characters interacting with humans are mostly drawn from comic strips (like Dick Tracy, Garfield, and Life in Hell), and not classic animated cartoons… and Roger Rabbit? He’s actually dead (see also: creepy Frank, above). Roger gets murdered early on in the book, leaving private eye Eddie Valiant to track down his killer. Apparently, Steven Spielberg and Disney weren’t so into the whole dead-cartoon-rabbit thing, and so the character was resurrected and a monster hit was born (along with at least one amazing dance move).

The White Rabbit and the March Hare (Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland)

I’ve always thought of the White Rabbit as a bit of a pill; he’s neurotic and occasionally pompous and always in a hurry, but it’s hard to deny his pop cultural notoriety. “White Rabbit” has been a trippy byword for psychedelic drug use since the 1960s, as well as a recurring trope in both Lost and the Matrix movies (apparently, he moonlights as a harbinger of not-very-satisfying conclusions…). The March Hare, on the other hand, is simply certifiable (Lewis Carroll was playing on the English expression “mad as a March hare,” making him the perfect companion for a certain wacky, riddle-loving Hatter). In the book, it’s the Hare, not the Rabbit, that loves to party—and maybe they were only drinking tea when Alice first encounters the March Hare, but something tells me he would fit right in with a certain clique of ancient Aztec party bunnies…

Gargantuan Mutant Killer Rabbits (Night of the Lepus)

Based on the Australian science fiction novel The Year of the Angry Rabbit, the movie version moved the setting to Arizona, leaving the book’s satirical elements behind while retaining the basic premise: giant, mutant carnivorous rabbits threatening humans. Released in 1972, Night of the Lepus was a monumental flop, completely panned by critics for its horrible plot, premise, direction, acting, and special effects, and for utterly failing to make giant bunnies seem scary (presumably forcing audiences to wait with bated breath another six years before they could be properly traumatized by the film version of Watership Down).

Dragonfly Bunny Spirits (The Legend of Korra)

![]()

Screenshot: Nickelodeon

Anyone familiar with Avatar: The Last Airbender and The Legend of Korra know that the world of the avatars is full of amazing, often adorable creatures (baby saber-tooth moose lions, anyone?). But even with all the competition, Furry-Foot and the other dragonfly bunny spirits rate pretty high on the all-time cuteness scale. Since they generally do not appear to people unless they sense a strong spiritual connection, the dragonfly bunny spirits were initially only visible to Jinora (the young daughter of Tenzin/granddaughter of Aang and Katara). Eventually, Jinora urged the spirits to reveal themselves to Tenzin, Korra, Bumi, and the rest of her family, and they helped the group gain access to the spirit world. When exposed to negative energy, dragonfly bunny spirits may turn into dark spirits, but otherwise make great pets and I totally want one.

Jaxxon (Star Wars)

![]()

For those of you who might not be familiar with the Lepi (Lepus carnivorus), they are the sassy sentient rabbits of the Star Wars Expanded Universe, native to the planet Coachelle Prime (although their rapid breeding rate quickly led them to colonize their entire star system, because…rabbits.) Jaxxon is probably the most famous member of the species—a smuggler, Jax joined Han Solo in defending a village under attack along with several other mercenaries, collectively known as the Star-Hoppers of Aduba-3. The Star-Hoppers fended off the superior forces of the Cloud-Riders and defeated the Behemoth from the World Below, saving the village, after which Jaxxon returned to smuggling and his ship, the Rabbit’s Foot. Having fallen into relative obscurity over the years, he was one of the first characters created outside of the films for the Marvel Star Wars comic series, as an homage to Bugs Bunny (who often addressed random strangers as “Jackson” in the old Warner Brothers cartoons… hence the name.)

The Were-Rabbit (Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit)

![]()

Screenshot: DreamWorks/Aardman Animations

As part of his humane pest control business, eccentric inventor Wallace attempts to brainwash a group of rabbits out of stealing vegetables, but during the process things go awry and Wallace ends up with one of the bunnies fused to his head. His highly intelligent dog, Gromit, saves the day (as usual), but afterwards both Wallace and the rescued rabbit (now called “Hutch”) exhibit strange behavior. It’s not long before the village is being terrorized by a giant, vegetable-crazed Were-Rabbit, and Wallace and Gromit must solve the mystery before the monster can ruin the annual Giant Vegetable Competition…and if you haven’t seen this movie, you probably should. Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit was only the second non-American movie to win the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, and it was the very first stop-motion film to win, which is pretty impressive. Plus it’s chock-full of claymation bunnies, of course.

Willahara (Grimm)

![]()

Screenshot: NBCUniversal

Speaking of were-rabbits, the Willahara are a form of Wesen, magical beings whose true form can be seen by the supernaturally gifted humans known as Grimms. As featured in the episode “Bad Luck” (S4, Ep. 14) the Willahara woge into humanoid fur-covered rabbits, essentially, known for being gentle, passive, and very fertile. It’s this last characteristic that leads to Willaharas being hunted—in the show’s twist on the superstition about rabbit feet being lucky objects, Nick (the titular Grimm) and his crew must stop a murderer targeting Willaharas (and using their severed feet as a grisly fertility aid. So…yikes.)

Peppy Hare (Star Fox)

Okay, full disclosure: I’ve never actually played Star Fox, but when I mentioned this post to Chris and Sarah here in the Tor.com offices, they immediately started yelling about Peppy Hare and wouldn’t stop playing clips of all his weird wingman advice and catchphrases until I added him to the list. So here we go: Peppy Hare is a member of the original Star Fox team who serves as a mentor to the game’s protagonist, Fox McCloud. According to Chris and Sarah, Peppy is way more awesome than the team’s other wingmen, Slippy Toad (who is “the worst”) and Falco Lombardi (who does nothing but criticize, even when you save his life. Jerk.) Peppy wants you to do a barrel roll. Always. You should probably listen to him.

Miyamoto Usagi (Usagi Yojimbo)

![]()

Created by Stan Sakai in the early 1980s, Usagi Yojimbo follows the adventures of Miyamoto Usagi, a rabbit ronin, as he wanders about on a warrior’s pilgrimage, occasionally serving as a bodyguard. Set in Japan during the early Edo period, the series was lauded for its attention to detail in terms of period architecture, weaponry, clothing, etc., and drew heavily on Japanese samurai films (particularly the work of Akira Kurosawa, given the title) as well as Japanese history and folklore. Based on the legendary swordsman Miyamoto Musashi, Usagi is a formidable warrior in adorable rabbit form, and is frequently ranked among the greatest comic book characters of all time (by Wizard magazine, Empire magazine, and IGN, among others).

Max (Sam & Max)

![]()

Screenshot: LucasArts

Described as a weird “hyperkinetic rabbity thing,” Max is the smaller, more aggressive member of the infamous crime-fighting duo known as Sam and Max: Freelance Police. Along with Sam, a wisecracking, fedora-wearing dog, Max works as a private investigator with a healthy disrespect for the law; where Sam is grounded and professional, Max is gleefully violent and maybe a tad psychotic (in a fun way!) He’s a lagomorph who gets things done, and you really don’t want to mess with him. Sam & Max have attracted a rabid cult following over the years, initially appearing in comics, then a series of video games and TV series in the late 90s—I first encountered them in the now-classic LucasArts adventure game Sam & Max Hit the Road, which I can’t recommend highly enough—12-year-old me was a little obsessed with it, back in the day, and I’m pretty sure it holds up, even now….

Basil Stag Hare (Redwall)

![]()

Screenshot: Nelvana

Fans of Brian Jacques’ Redwall series will recognize this handsome gentleman as Basil Stag Hare of the Fur and Foot Fighting Patrol. A loyal ally and expert in camouflage, Basil assists Matthias and the other denizens of Redwall Abbey when trouble threatens, playing a key role in several rescue missions, and is known for both his appetite and his battle cry, “Give ‘em blood and vinegar!”

Bucky O’Hare

The eponymous hero of his own comic book series as well as an animated TV series and several video games, Bucky O’Hare is the captain of The Righteous Indignation, a spaceship in service of the United Animals Federation. The Federation is run by mammals and exists in a parallel universe from our own, where they are at war with the evil Toad Empire (ruled by a sinister computer system known as KOMPLEX, which has brainwashed all the toads. Natch.) In both the original comics and the spin-off media, Bucky fearlessly leads his crew—which includes a telepathic cat, a four-armed pirate duck, a Berserker Baboon, a one-eyed android named Blinky, and a presumably confused pre-teen who becomes stranded in “the Aniverse”—against the rising toad menace. Rumors that he may be closely related to Jaxxson remain unconfirmed…

Captain Carrot and His Amazing Zoo Crew!

![]()

While this DC Comics series only lasted from 1982 to 1983, this wacky band of characters still make occasional cameos in the DC universe, appeared in an arc of Teen Titans, and a reprint of their entire 26 issue series was released in September 2014. Captain Carrot (aka Roger Rodney Rabbit of Gnu York—no relation to the other Roger, presumably) leads the intrepid Zoo Crew ask they face an array of sinister anthropomorphic villains and, apparently, a world filled with animal-related puns (there’s a character named after Burt Reynolds. His name is “Byrd Rentals.” He gains superpowers when a meteor fragment strikes his hot tub and becomes Rubberduck.) Captain Carrot, on the other hand, replenishes his powers by eating cosmic carrots, gaining super-strength, heightened senses, endurance, and of course, super-leaping abilities.

Mr. Herriman (Foster’s Home For Imaginary Friends)

The oldest imaginary friend at Foster’s, Mr. Herriman is a stickler for the rules, is well-meaning but often pompous, and can generally come off as a bit stiff (although he also has a wild-and-crazy hippy-esque alter ego named “Hairy,” so at least he gets to let loose sometimes). A six-foot-tall rabbit sporting formal wear, a monocle, and a top hat, the very proper, very English Mr. Herriman is obsessed with keeping order and protecting Madame Foster, who created him when she was a small child in the 1930s. He remains singularly devoted to his creator, even deigning to perform the “Funny Bunny” song and dance that delighted her as a girl (but only behind closed doors, where no one can see him cavorting about…)

Binky, Bongo, Sheba, et al. (Life in Hell)

![]()

Image: Matt Groening

You can’t really separate the Simpsons from their origins in Life in Hell, the long-running comic strip dedicated to Matt Groening’s ruminations on life, love, work, death, and all the fear, humor, irritations, and anxiety that existence entails. Beginning in 1977, Groening’s comics centered on the rabbit Binky (generally neurotic and depressed) and his son Bongo (a young one-eared rabbit, full of mischief, curiosity, and inconvenient questions), as well as Binky’s girlfriend Sheba and identical humans Akbar & Jeff. Groening would also represent himself and his sons Will and Abe in rabbit form in the strip, which finally ended its run in 2012. Often darker, weirder, and more introspective than The Simpsons, I loved reading the Life in Hell books and comics in the free Philadelphia City Paper as a kid—Groening’s rabbits were both funny and oddly therapeutic, perfect for weird kids, smartass teens, and stressed-out adults alike.

Suzy, Jack, and Jane (David Lynch’s Trio of Humanoid Rabbits, Rabbits / Inland Empire)

In 2002, David Lynch released a series of avante-garde video films featuring a trio of humanoid rabbits, which the director refers to as a “nine-episode sitcom.” The horror-comedy vibe of these shorts is reflected in the series’ creepy tagline, “In a nameless city deluged by a continuous rain…three rabbits live with a fearful mystery.” The nature of that mystery is never quite revealed, as the rabbits mainly wander around the sitcom-style set uttering curious non-sequiturs or reciting esoteric poetry; they are occasionally interrupted by a random, effusive laugh track. The rabbits are played by Naomi Watts, Laura Harring, and Scott Coffey (all of whom appeared in Lynch’s Mulholland Drive), and the set and some footage from the series were used in Inland Empire, lending fuel to the theory that all of Lynch’s films are somehow interrelated in some way…

Various Bunny-Based Pokémon

![]()

Screenshot: The Pokemon Company

I am very much not an expert on Pokémon, but I know cute when I see it, and frankly I am not made of stone. So, whether you prefer to go old-school with blue and bubbly Azumarill (the first ever rabbit-esque Pokémon), or if you’re more into the adorable Buneary or the floppy-eared Lopunny, or maybe the absolutely precious and mischievous Scorbunny, there are some truly excellent options, here—I’ll let you pick your own favorites (and argue about how loosely you want to define “rabbit-like”… personally, I think Wigglytuff totally counts. So freakin’ cute).

Bugs Bunny

![]()

Screenshot: Warner Bros

Last but not least, here’s Bugs: wily trickster, Warner Bros. royalty, and comedy icon. Bugs made his official debut in 1940’s A Wild Hare, a huge critical and commercial success (it even got an Oscar nomination), with the legendary Mel Blanc providing the bunny’s now-famous New Yawk accent and delivering his catchphrase, “What’s up, Doc?” Since then, the rascally rabbit has starred in countless cartoons, movies, video games, even commercials, satirizing and spoofing decades worth of popular culture and accumulating plenty of SF/F cred along the way. Bugs has been consistently foiling Marvin the Martian in his attempts to destroy the Earth since 1948, while still finding time to torment a certain vengeful Norse demigod in What’s Opera, Doc? All that, and he still looks great in a wig—Bugs is a true paragon of rabbitkind.

***

I could go on, but I don’t have much to say about Radagast’s sleigh-pulling Rhosgobel Rabbits (big! fast! furry!), although they certainly deserve an honorable mention along with Mr. Bunny Rabbit (of Captain Kangaroo), the psychotic-but-adorable Bun-bun (Sluggy Freelance), Mr. Bun (aka Pauly Bruckner in The Unwritten), and Tim Conway’s performance as F. Lee Bunny on The Carol Burnett Show. In the meantime, here’s what we’ve learned: Don’t underestimate bunnies. They’re so much more than carrot-loving, Trix-shilling, twitchy little furballs: sometimes they’re mystical, sometimes they’re trying to stave off the apocalypse; sometimes they just want to chew your face off. Plus, they multiply almost as fast as Tribbles (but with less purring and many, many more teeth). If they ever do end up taking over the world, it’s not like we haven’t been warned….

![]()

An earlier version of this article appeared on Tor.com way back in April 2011, and has been updated a number of times since.

Bridget McGovern is the Managing Editor of Tor.com. She wasn’t really all that screwed up by Watership Down, if you don’t count the fact that she just stays up nights writing frantically about bunnies (and will always maintain a vague but potent distrust of Art Garfunkle).

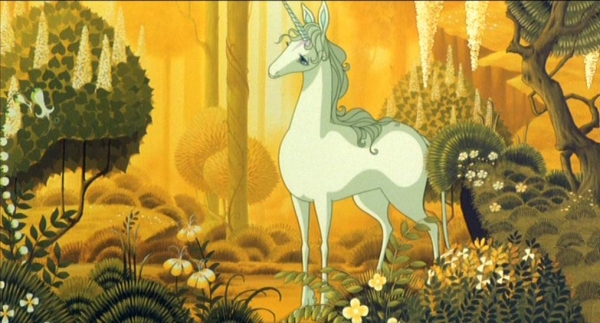

Out on the road, the unicorn is mistaken for a horse by men and sees no signs of her lost kin until she crosses paths with a rapturous, half-mad butterfly who recognizes her and names her, between reciting frantic snippets of songs, poetry, and jingles.* In a fleeting moment of clarity, he tells her that her people have been chased down by a creature called the Red Bull, and so she sets out again, only to find herself recognized and captured by a seedy hedge witch. Outfitted with a false horn (so that she may be seen by unknowing customers for what she truly is), the unicorn is put on display as part of Mommy Fortuna’s Midnight Carnival, a shabby collection of counterfeit monsters and one other true immortal creature: the harpy,

Out on the road, the unicorn is mistaken for a horse by men and sees no signs of her lost kin until she crosses paths with a rapturous, half-mad butterfly who recognizes her and names her, between reciting frantic snippets of songs, poetry, and jingles.* In a fleeting moment of clarity, he tells her that her people have been chased down by a creature called the Red Bull, and so she sets out again, only to find herself recognized and captured by a seedy hedge witch. Outfitted with a false horn (so that she may be seen by unknowing customers for what she truly is), the unicorn is put on display as part of Mommy Fortuna’s Midnight Carnival, a shabby collection of counterfeit monsters and one other true immortal creature: the harpy,  As an extension of this humor, Beagle constantly plays with the reader’s sense of time and place in a hundred small ways. In spite of the quasi-medieval setting of the tale with its peasants, knights, and kings living in stony, witch-raised castles, he sprinkles in the oddest details: Haggard’s men-at-arms wear homemade armor sewn with bottle caps; elsewhere, a bored princeling flips through a magazine; Mommy Fortuna talks about her act as “show business,” and Cully invites Schmendrick to sit at his camp fire and “[h]ave a taco.” Moments like these don’t jolt you out of the story—they’re more like a gentle nudge in the ribs, reminding you that there’s much more going on under the cover of the classic quest narrative driving things forward.

As an extension of this humor, Beagle constantly plays with the reader’s sense of time and place in a hundred small ways. In spite of the quasi-medieval setting of the tale with its peasants, knights, and kings living in stony, witch-raised castles, he sprinkles in the oddest details: Haggard’s men-at-arms wear homemade armor sewn with bottle caps; elsewhere, a bored princeling flips through a magazine; Mommy Fortuna talks about her act as “show business,” and Cully invites Schmendrick to sit at his camp fire and “[h]ave a taco.” Moments like these don’t jolt you out of the story—they’re more like a gentle nudge in the ribs, reminding you that there’s much more going on under the cover of the classic quest narrative driving things forward. Both Haggard and Lír are instantly transfixed by Amalthea—Haggard suspects something of her unicorn nature, while Lír attempts every heroic deed in the book, from ogre-fighting to dragon-slaying to damsel-rescuing, in an attempt to get her attention. He turns himself into a mighty knight, but she does not notice him at all, too lost and confused in her new human body. Time passes, Molly and Schmendrick are no closer to discovering the whereabouts of the Bull or the missing unicorns, and Amalthea is so distraught and plagued by nightmares that she finally turns to Lír, falls in love, and begins to grow more and more human, gradually forgetting herself and her quest.

Both Haggard and Lír are instantly transfixed by Amalthea—Haggard suspects something of her unicorn nature, while Lír attempts every heroic deed in the book, from ogre-fighting to dragon-slaying to damsel-rescuing, in an attempt to get her attention. He turns himself into a mighty knight, but she does not notice him at all, too lost and confused in her new human body. Time passes, Molly and Schmendrick are no closer to discovering the whereabouts of the Bull or the missing unicorns, and Amalthea is so distraught and plagued by nightmares that she finally turns to Lír, falls in love, and begins to grow more and more human, gradually forgetting herself and her quest. Over the course of this most recent reread of the novel, I’ve been thinking that it’s well and good to call a book a classic and give it a place of pride on your shelves and pick it up now and again when the mood strikes you, but there are certain books that should be shared and talked about far more often than they are. The Last Unicorn is not a difficult book—it is as smooth and graceful as its mythical protagonist, satisfying, resonant, self-contained, with hidden depths. It is a pleasure to read, even in its most bittersweet moments, and I wonder if, in some strange way, it gets overlooked at times because of its pleasurable nature.

Over the course of this most recent reread of the novel, I’ve been thinking that it’s well and good to call a book a classic and give it a place of pride on your shelves and pick it up now and again when the mood strikes you, but there are certain books that should be shared and talked about far more often than they are. The Last Unicorn is not a difficult book—it is as smooth and graceful as its mythical protagonist, satisfying, resonant, self-contained, with hidden depths. It is a pleasure to read, even in its most bittersweet moments, and I wonder if, in some strange way, it gets overlooked at times because of its pleasurable nature.

He was also a one-eyed albino who went about cloaked and hooded to protect him from the light and (spoilers for A Dance with Dragons), he lives on as the three-eyed crow that appears to Bran Stark after his accident. When Bran and the Reeds finally reach his cave, Brynden appears not as a crow but as the last greenseer, a skeletal figure entangled in the roots of a weirwood tree who teaches Bran how to develop his own gifts as a seer. At this point in time, Bloodraven would be around 125 years old (but looks pretty great for his age, if you ignore the whole “weirwood roots poking through his bones and empty eyesocket” thing).

He was also a one-eyed albino who went about cloaked and hooded to protect him from the light and (spoilers for A Dance with Dragons), he lives on as the three-eyed crow that appears to Bran Stark after his accident. When Bran and the Reeds finally reach his cave, Brynden appears not as a crow but as the last greenseer, a skeletal figure entangled in the roots of a weirwood tree who teaches Bran how to develop his own gifts as a seer. At this point in time, Bloodraven would be around 125 years old (but looks pretty great for his age, if you ignore the whole “weirwood roots poking through his bones and empty eyesocket” thing).